What a time it is to be a children’s book author in the United States.

A lot of people are talking about children’s books these days. Not, unfortunately, about how children’s literature is absolutely booming with creativity, diversity, boldness, and ideas—which it is—but instead because book banning is once again en vogue in the worst parts of society, for all the worst reasons.1 It’s neither difficult nor particularly interesting to discern what’s motivating proponents of book banning: the political power derived from stoking moral outrage, the chance to bully and threaten anybody they don’t like while pretending it’s about protecting children, and the fear that their children might read something that will make them think, “Wow, my parents are astonishingly bigoted and have very bad ideas about many things.”

It’s unfortunate that children’s literature only makes the news when people are being terrible about it. I think it changes the way we talk about children’s books, and not for the better. When we’re forced to defend books with diverse characters by insisting it does kids good to see themselves in literature, we’re overlooking the value of seeing characters nothing like themselves too. When we’re forced to defend darker, more mature subject matter by referencing how many kids experience similar challenges in real life, we’re overlooking the value of letting kids read about things that haven’t happened to them and might never happen, but still expand their understanding of the world and the people in it. When we’re forced to defend against charges of grooming or indoctrination—well, many of us pour a very large drink and cry, because there is only so much stupid cruelty anybody can take.

It’s regrettable that people who hate children’s literature so often define the terms by which we talk about it, because I think there is a fascinating conversation to be had about the ways children’s books influence and change young readers.

Because they do. Of course they do. Everything we read, at any age, influences us. Changes us. Introduces us to new ideas. Generates new emotions and thoughts. Rewires previously comfortable pathways in our minds. And it keeps happening, over and over again, as we grow and mature and change.

The fact that books change us shouldn’t be scary. It isn’t scary, not unless you are terrified of other people, such as your children, having ideas that you cannot control. Sometimes it’s unsettling, and sometimes it’s uncomfortable. It’s very rarely straightforward. But it’s also splendid, because while we only ever get to live one human life, books offer up infinite experiences to anybody who goes looking. We should be able to talk about this—about ourselves and about young readers—in a way that isn’t dictated by idiots who believe that a picture book about an anthropomorphized crayon represents society’s worst degeneracy.

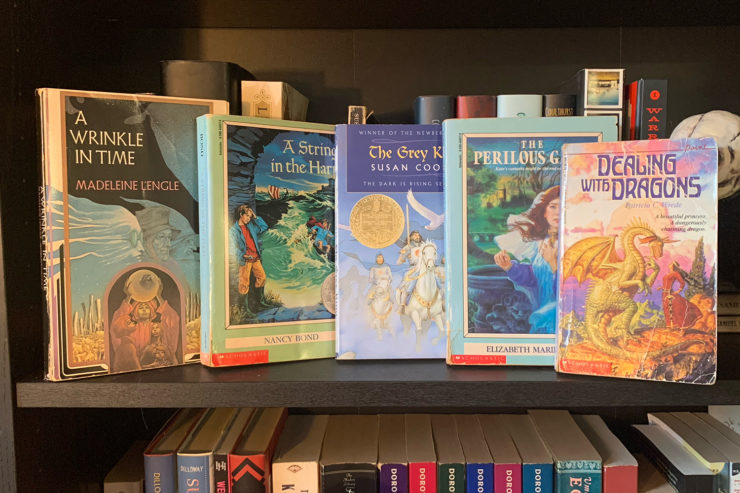

I’ve been thinking a lot about the books I read as a child that still resonate with me today, the books that contain certain scenes or arcs that I still think about, decades later, because of how deeply they impacted me. And I’m not talking about issue-centered books that book-banners are so afraid of. Sure, I read Number the Stars and The Slave Dancer and Maniac McGee, and I took pride in scouring the ALA’s list of frequently challenged books to find new things to read, because I was an extremely bookish ’80s child of a schoolteacher growing up in a house full of heady sci-fi and fantasy, ponderous literary classics, outrageous teen horror, and Scholastic paperbacks.

But, let’s be real, I mostly wanted to read books about people having exciting, strange, mysterious, or magical adventures. That’s still mostly what I want to read and write as an adult, so I like to think about the lasting and unexpected ways they influenced me when I was young. I talk about a few of them below: not just the books that got their claws in and never let go, but the specific scenes that I still think about years later. These are stories full of fairies, dragons, space travel, time travel, battles between good and evil—and much-needed insight into being a person in this world that awkward tween me, braces and uncombed hair and bad attitude and all, didn’t even know she was looking for.

[Note: This list contains a lot of spoilers for books and series that have been widely read for decades…]

The Perilous Gard by Elizabeth Marie Pope

This 1974 book is an adaptation of the story of Tam Lin, set in the 1550s, about a teen girl named Kate, who is a lady-in-waiting to Princess Elizabeth. The book begins as Kate is sent into a genteel sort of exile because of some political foolishness on the part of her younger sister. But this is not a story about court politics. It’s a story about fairies and how strange and terrifying they can be.

It would probably be categorized as YA if it were published now, because today’s marketing categories would not allow a children’s book to feature a romance that leads to an engagement. And that’s unfortunate, because it’s perfectly suitable for younger readers (and modern publishing’s perspective on the role of romance in stories is deeply flawed, to literature’s detriment, but let’s not get into that right now). It’s a moment regarding this romance that I still find myself thinking about as particularly influential on tween me, some thirty-plus years after I first read it.

At the very end of the novel, after Kate has escaped the fairy realm, rescued her very grumpy Tam Lin, and returned to the mundane world, she does not expect a romantic happily-ever-after, because romances don’t like look whatever she and her love interest have going on. She didn’t save him with fierce devotion alone, after all; she saved him by making fun of him so much that his annoyance broke the fairy spell (#couplegoals). And the Queen of the Fairies, who has been thwarted but not defeated, takes advantage of this, as fairies as wont to do, by offering Kate a love spell.

Kate refuses, because she knows that love must be freely given to be genuine, and almost immediately she realizes that the Lady was not offering a gift at all. It was both a test and a subtle act of revenge. The love is requited, Kate is going to get what she wants—but if she had accepted the love spell, she would have believed it all to be a magical lie. The test she passed, but the revenge she denied.

I think about that a lot not just because it’s a fabulous way to end the book, but because of the sheer insidiousness of what the Lady was offering. I didn’t realize it at the time, when I was a kid, but over the years I have thought a lot about what it says about powerful people who will offer what is not theirs to give, what is perhaps not even in their ability to give, and what it means when they call those gifts generosity when they are, in truth, only a form of control.

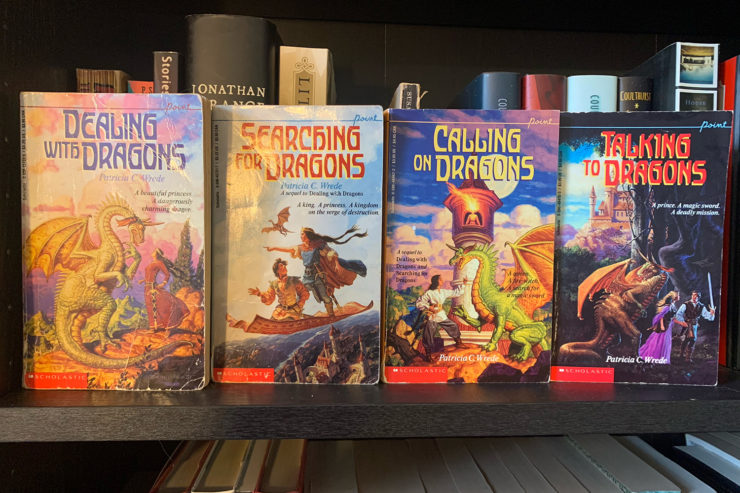

Dealing With Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede

This is the first book in a four-book series2 about a bored princess who runs away from home to get herself kidnapped by dragons, becomes embroiled in dragon politics, meets many strange and interesting people, marries the eccentric king of an enchanted forest, keeps having more adventures, and finally raises a son to send off on adventures of his own.

This is lighthearted fantasy humor at its finest: embracing all the tropes and trappings of fairy tale fantasy, while also poking fun at them in a way that is never snide, always loving. I reread this one the other day, because I was thinking about the premise—bored princess runs away because she hates boring princess things—and wondering why I didn’t remember it as a tiresome example of that pervasive plague of the 1990s: Not Like Other Girls Syndrome. I’m not sure I would have noticed as a tween, and I wanted to see if my memories of the book had been softened by rose-tinted nostalgia.

To my delight, I discovered that it is more or less exactly as I remember. It turns out that even the not like other girls aspect of the story is part of the deliberate subversion. As Princess Cimorene settles into her new life and meets more and more people, it becomes clear that chafing against the expectations and roles assigned by society is something shared by all kinds of people.

This is especially obvious when Cimorene makes friends with another princess “captive,” Alianora. While Cimorene has fought her entire life against being a perfect princess, Alianora has spent her entire life struggling to be a perfect princess—and both of them have failed in the eyes of their society, just as the knights and princes who don’t want to kill dragons are also failures in this social system. It’s a friendly, silly moment in the story, but it still struck me with the realization that no matter what you do to fit in, no matter how hard you try to please, somebody is going to disapprove. So you should just do what you want.

I read this book when I was in middle school, which was, for a thirteen-year-old girl growing up in a 1990s hotbed of toxic American Evangelicalism, essentially a noxious stew of nothing but pressure to fit into predefined roles. It was so reassuring to read a book in which the problem is not with the girls themselves, only with the pressure to fit into roles that do not suit them and do not make them happy. The fact that it did this in such a fun way, without any of the ponderous self-seriousness of an Afterschool Special, only made it better.

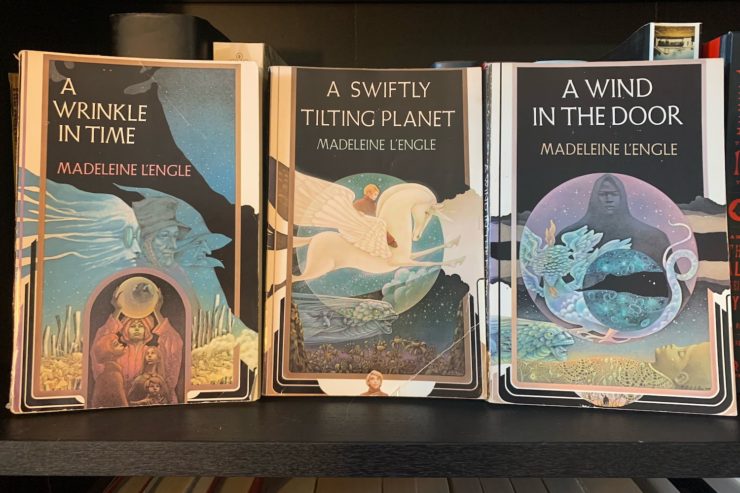

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

This book was many people’s gateway drug into big-ideas, high-concept SFF, and let us not forget how gloriously weird it is. It is so incredibly weird! Some kids travel across space to an alien planet with the help of some old ladies who are actually stars to rescue their dad from a pulsating psychic brain amidst a cosmic fight between good and evil? Sure, why not.

But even more that the weirdness, what I’ve always loved most is the wonderful creepiness that underlies the story. The very first line is, “It was a dark and stormy night,” but it goes so far beyond Meg Murry feeling furiously sorry for herself in her bedroom. (Which was so relatable to angry tween me!) (And adult me.) The one scene that has always stuck in my mind is the walk through the neighborhood when the kids first arrive on Camazotz3.

What they find on this alien planet is a nightmare version of suburbia. A Wrinkle in Time was published in 1962, and suburban tract housing evolved in the 1940s following WWII, so neighborhoods of the sort found on this evil planet were barely older than the story’s main characters at the time. Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin walk through this neighborhood, where every house looks the same, every child skips rope or bounces a ball to the same rhythm, and every mother opens the front door to call every kid home at the exact same time, in the exact same way.

The extreme conformity is unsettling, yes, but it steps up a notch when one kid fumbles his ball and runs inside before retrieving it. When our characters knock on the door to return the ball, the mother and son respond with a powerful, visceral, bone-deep fear. Meg and the boys don’t understand this fear yet, but they recognize it and know it’s a symptom of something very, very bad.

And that’s why it’s such a powerful scene: because the reader is right there with them, not yet understanding, but still feeling the dread of what it means. When I first read this book, I certainly did not comprehend L’Engle’s complex religious and philosophical thoughts on the nature of good and evil, but, boy oh boy, did I ever get the message that absolute conformity enforced by suffocating fear for what anybody claims is the “greater good” is a really bad thing.

A String in the Harp by Nancy Bond

This 1976 novel tells the story of a family that moves to Wales in the aftermath of their mother’s death, where the children become magically connected to the legendary bard Taliesin. It’s an odd fantasy story in many ways, because it’s not quite a time travel book, really, nor is it quite a portal fantasy, but it has elements of both.

The story focuses particularly on teenaged Jen, who joins her family in Wales for the Christmas holiday only to find them more or less in emotional shambles, and on middle child Peter, the one who accidentally stumbles upon a time-bending magical artifact. Their family is not doing well. Their father buries himself in his work; Jen is thrown immediately into a caretaking role that she rightfully finds frustrating and overwhelming; Peter is deeply depressed and copes by lashing out and isolating himself; and their younger sister Becky is trying very hard to make the most of things, which is no easy task when all of the older people in your life are miserable all the time.

About halfway through the book the family reaches its emotional nadir; they’re all frustrated, hurt, and pulling in different directions, without any real idea how to get through it. They spend a night home together during a fierce winter storm, during which they see strange lights on the bog of Cors Fochno. Only Peter knows that what they are seeing is a battle that took place on the bog more than a thousand years ago, and he knows nobody will believe him if he tells them. But there is no denying that they all see it, as do their neighbors and other townspeople. It’s an eerie, unsettling scene, with the strained quietness of an unhappy family witnessing an oddity they want to rationalize away, clashing with Peter’s magic-bestowed knowledge of a terrible battle—knowledge that he clings to so fiercely it’s pulling him away from his real life.

It’s a turning point in the story, and it has always stuck with me precisely because it’s a moment that is shared. The three children, their father, the neighbors who have welcomed them, and the village in which they don’t quite fit, they all witness it together: lights in the darkness, fires where none should be, shadows in a storm that came from nowhere. It’s a step toward breaking down the terrible loneliness the main characters are suffering, in the form of an ancient myth come to life.

I don’t know if the book ever uses the word depression, and it certainly doesn’t use words like parentification and emotional labor, but those elements are all there, even if the vocabulary isn’t. When I first read it, I wasn’t thinking about using fantasy to tell very real stories about very real problems in children’s lives. I didn’t realize it was talking about things I wanted to talk about—even though I didn’t relate to their circumstances precisely—without knowing how to do that. But in retrospect it’s obvious that’s why it appealed to me.

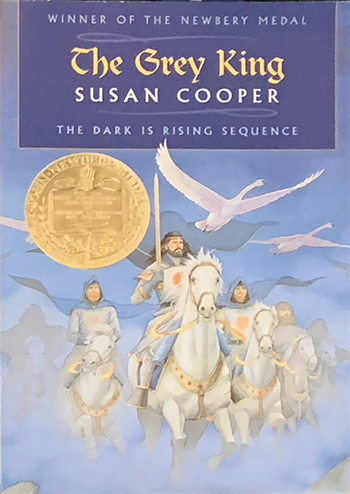

The Grey King by Susan Cooper

Combined with the above, this book convinced me early in childhood that Wales is obviously a magical place, and thirty-some years later I’ve not been dissuaded from that belief. This is the fourth book in Cooper’s Arthurian-Celtic-English-Welsh-Norse-folkloric-mixed-bag The Dark Is Rising sequence, and it’s my favorite of them, because the dog dies.

That makes me sound like a monster. Let me explain.

Series protagonist Will Stanton, who in The Dark Is Rising learns that he is a warrior in the eternal battle between good and evil and handles it with rather more equanimity than most eleven-year-olds would, is sent off to his aunt’s farm is Wales to recover from a serious illness. There he meets Bran Davies, a strange, lonely local boy whose only friend is his dog, Cafall. (If you know your canine pals from folklore, that name might ring a bell.) The boys get caught up in said ongoing battle between good and evil, and there are a lot of escalating magical encounters, culminating in a horrifying scene where, via some magical trickery, the forces of evil delude some local men into thinking Cafall has slaughtered a sheep right before their eyes. One of these men, the local asshole Caradog Prichard4, shoots the dog to death right in front of Bran and Will and everybody else.

When I read this as a kid, I wasn’t shocked because the dog got killed. The dog always dies in classic children’s literature!5 No, what stood out to me was how thoroughly nasty the whole ordeal is in such an ordinary, unmagical way. There might be magical trickery involved, but the sadism and self-satisfaction that drives Prichard to kill a beloved dog right in front of its eleven-year-old owner is entirely human. When talking to Will about it afterward, a neighbor explains the history of hatred between the families involved; it’s a history that involves an attempted rape, a violent assault, and years of seething jealousy. Men like Prichard don’t need to be active agents of the forces of evil, because they’re all too willing to do evil’s work of their own volition, without even being asked.

There another thing that’s always struck me about this scene and its aftermath, and that’s the fact that Bran Davies, like Meg Murry in A Wrinkle in Time, is allowed to be angry. Not angry in the way that fictional children are temporarily permitted in the face of wrongdoing, as part of learning a lesson, but angry in a wild and selfish way, lashing out at the wrong people, wielding their hurt as weapons. That was a powerful thing to read as a child who was often very angry and was just as often told not to be so emotional about everything.

Now, with the benefit of a few more decades of life experience, I recognize that kids often have very good reasons to be angry. I’m glad I had books to tell me that was okay long before anybody ever said it to me in person.

***

The books we read as children do change us as people, because all literature that we read changes us, whether we want it to or not—and we should want it to. Opening up our minds to fill them with stories outside of our own experiences is one of the best parts of being human. The ways they influence us are not always obvious or straightforward, but that’s part of the joy.

I wish that joy could be a bigger part of what we could talk about, on a broad scale, when we talk about children’s literature. Every one of us is a tapestry of influences, impressions, and ideas that have lingered in our mind for years, challenging us and surprising us in ways that we don’t always recognize until much later—and right there, at the heart of that tapestry, are the books we read when we were young.

Buy the Book

Hunters of the Lost City

Kali Wallace studied geology and earned a PhD in geophysics before she realized she enjoyed inventing imaginary worlds more than she liked researching the real one. She is the author of science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels for children, teens, and adults, including the 2022 Philip K. Dick Award winner Dead Space. Her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, F&SF, Asimov’s, Tor.com, and other speculative fiction magazines. Her newest novel is Hunters of the Lost City, a middle grade fantasy adventure out now from Quirk Books. Find her newsletter at kaliwallace.substack.com.

[1]According to a recently released PEN America survey (which is worth reading: https://pen.org/banned-in-the-usa/), over a thousand books are banned in schools and libraries in 86 school districts in 26 states, which is 2,899 schools with about two million students. They can only include cases they know about that fit their criteria, so it is almost certainly an undercount, and does not include so-called “soft” censorship where educators simply choose not to order or provide access to certain books. But there are some 13,800 school districts in the country. This trend is deeply concerning but not anything close to universally popular. Don't let anyone tell you it is. The illusion of widespread support is part of the propaganda.

[2]Chronologically, although it was published second, in 1990. The fourth chronological book in the series, “Talking to Dragons,” was actually written and published first (1985). I did not know this when I was a kid. I read them in story-order, as did many people, I think, as my Scholastic paperback clearly identifies “Dealing With Dragons” as Book One.

[3]I just now googled “Camazotz” for the first time and learned that it is the name a monstrous bat god from Mayan mythology.

[4]Perhaps named in reference to, but not to be confused with, the real-life Welsh poet of the same name, who as far as I know never killed a dog.

[5]“Where the Red Fern Grows.” “Old Yeller.” “Sounder.” “Island of the Blue Dolphins.” Just the ones I can think of offhand. I'm sure there are more.

I, too, read all of these books as a child, and they were all enormously influential in ways I never quite put into words– but Kali Wallace does such a great job of it here. (and in so doing evokes a real fondness for someone else who’s read and loved the same books. I’ve never met anyone who’s read A String in the Harp!)

I do note an issue with footnotes 1 and 3 — has some content been lost?

@1: Thank you–the footnotes should be fixed!

I’m a GenXer and the only book my folks kept me from reading was Jonathan Livingston Seagull, but it wasn’t that big a deal–just bemusing for a few hours and then I went back to what I usually read, which included biographies (LaSalle, WC Handy, George Washington Carver, Anne Sullivan Macy, Molly Pitcher, Abraham Lincoln, Ben Franklin, Sandy Koufax, Queen Isabella etc. etc. etc.), autobiographies (Helen Keller, and Anne Frank’s Diary which I’m calling an autobiography ’cause it is, really!), children’s books, and YA. Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism and her other works should definitely be in high school libraries.

First, wonderful article. I’ve been thinking a lot about the books I read as a child and how they influenced me. The scene from A Wrinkle in Time that most stuck with me was when the children go to Camazotz, and the witches give each child gifts to help them in the coming ordeal. Mrs Whatsit gift is to remind Meg of her faults, and to tell her that she thinks “they’ll come in very handy on Camazotz.” The idea that faults, including anger, can be strengths in times of crisis affected me deeply.

I am so glad to see Perilous Gaard on this list! I still re-read it

SO GLAD to see A String on the Harp here. An absolute favorite, re-read approximately 15 times, left me feeling wistful yet connected. Definitely a formative read.

As per the formative part of my childhood reading . . . I think it was the My Book House series with its works from other countries and bios, plus that one-volume book of stories from different cultures, all the bios, and historical fiction, that turned me into someone who is more interested in finding out what other people are like and in fiction what the characters are like rather than seeing myself in what I read, tho’ if there’s a point of contact about something serious, I will glom onto a book (oppression & emotional abuse in Montgomery’s The Blue Castle and Wells’ The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood).

What a marvelous essay, I plan to share the link to it – thank you!

Have you ever read Diane Duane’s Young Wizards series? Talk about life changing! And some of the most original ideas I have ever come across in any literature, not just children. Like the idea that it could be possible to redeem “the fallen one” – humanity’s concept of the creator of all evil, which exists in most world religions.

One of the most influential books in my life is Diamond in the Window, by Jane Langton. While the story has flaws, like emotionally blackmailing a 12 year old girl into thinking that wearing make-up is a gateway into turning into a horrible person, the book is magickal thinking. The story became my gateway into understanding how choices and decisions flow from one event to another.

My main influences as a 9-11 y/o kid (in the 80s, mind you) were Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain, the Dark Forces series of book (not Star Wars books, YA horror), and Time-Life’s Enchanted World series. By 12, it was all things Tolkien and Lovecraft.

If the The Dark is Rising series convinced you any part of Britain was a magical wonderland, shouldn’t it be Cornwall? Or the South-East, where the protagonist is from, although that’s probably the least magical part of the UK.

@12: No, Wales was clearly the place to be, despite a few other contenders. Besides The Grey King and The String in the Harp, there was Evangeline Walton’s Mabinogion retellings, and Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain, which was just Wales under another name (or one of its own names, close enough). And Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, and Jane Louise Curry’s Welsh Fair Folk in America series. And The Rising of the Lark by Ann Moray, which is historical fiction rather than fantasy but its Wales manages to be magical anyway (or so I thought at twelve))

Thank you, Kali Wallace, for this eloquent essay encouraging us to celebrate the joy of children’s lit, and the right for children to be angry and complicated. I read both “The Grey King” series and the “Dealing with Dragons” series as a kid, and scenes from them are definitely wedged in my brain. I like to think these smart, deep, and empathetic books have shaped who I became!

…I have fond memories of reading “Dealing with Dragons” aloud to my slightly-younger brother on a family vacation to rural Italy when I was perhaps 11 or 12. He would definitely have been old enough to read the book on his own, but he didn’t read for pleasure as a child. So instead, we spent the long summer evenings discovering the book together, me for the n-th time and him for the first.

I’m not sure siblings today do things like that very much, with omnipresent devices and streaming TV, but it’s a sweet memory of a time my brother and I enjoyed the same thing together. I’m grateful to have been reminded of it. :)

This is a wonderful essay, which I also will share with others. And may I vote for a future essay on modern publishing’s perspective on the role of romance in stories?

Re: footnote 5–If the dog has a long and difficult journey to make, it does not die. Lassie Come-Home. The Incredible Journey. The Hundred and One Dalmatians. Those are the dog books I read and loved in my childhood, so I was mystified at first years ago when I heard/saw the claim that “the dog always dies in classic children’s books”! What makes a classic, anyway? I note that both Sounder and Island of the Blue Dolphins won the Newbery and Old Yeller got the Newbery Honor. The Newbery judges, rather like the Oscar voters, have often valued Serious Drama (sometimes including Death) over, say, humor, fantasy and adventure.

I was so excited when I saw the article image and recognized every one of the books, although ironically, I read them all as a highschool or college student (technically my mom read A Wrinkle in Time to us when I was in grade school, but I remember little besides being confused if it was Mrs. Which or Mrs. Witch, and it was a new adventure when I returned to it later). I’m also surprised to find other people have read A String in the Harp since I found it by chance in my college library, assumed it was some obscure work, and, I’m sad to say, didn’t find it especially engaging. I should probably give it another pass and see I appreciate it more now.

For me, it’s snatches of books that stand out as influential in my childhood reading, like in the Silmarillion (which I read in my Tolkien craze) when Beren asks Finrod to help him on his quest, and Finrod realizes that he’ll die but goes anyway because Beren’s father saved his life, and I had this lightning flash of comprehension of why a life debt made sense. Or in The Hobbit when Bilbo takes the Arkenstone as his share and uses it to bargain for his friends’ lives at risk to his own, because while most everyone else (to be fair, Bard just wants refugee funding) is fighting over gold, he just wants everyone to be safe, and I learned that the most heroic acts don’t always require a sword.

A lot of the lessons I learned from books I read as child, though, I didn’t fully assimilate till years afterward of thinking about them and turning them over and integrating them into my ever-growing book world. This is one reason why I don’t think kids should be kept from reading a book because “they’re not old enough to understand it” (unless it’s disturbing material they’re not ready to handle, and even that should be handled on a case-by-case basis) because I sure as sure didn’t understand a lot of what I read the first time I read it, but that didn’t stop me from benefitting from reading it.

And yes, Wales is clearly jammed with magic (with the rest of the Isles in close contest) with fey folk around every corner just out of sight. In my mind I know they must have gas stations and bars with neon lights, but in my heart it’s misty green glens and old taverns with mysterious strangers all the way.

@@@@@ 12: 1 book set in Buckinghamshire, 2 books (the first of which contains relatively little magic) set in Cornwall, 2 books (containing quite a lot of the magic, and the appearance of King Arthur himself) set in Wales and forming the climax of the series.

Yeah, I think Wales is the logical one to imprint on as “magic place”, despite the fact that Buckinghamshire is clearly superior.

On the day after a legislator in my state stated in a legislative session that books removed from school libraries due to parent objections should be burned, this essay was a balm, so thank you. It reminded me of why this is such an important topic and so critical to keep pushing back at these attempts to make the worlds of children smaller and less wondrous. I especially appreciated the idea of yes, the books we read do change us, but that’s a wonderful thing that should be embraced. I read quite a few of the ones you mentioned from my school library. Would add for myself: The Blue Sword and The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley and The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander.

Re tragic ends for dogs in classic children’s books, Gordon Korman’s No More Dead Dogs (which contains no actual dead dogs) is a humorous take on that trope (it’s a middle school story, no fantasy involved). Early in the story, the first-person narrator complains, “The dog always dies. Go to the library and pick out a book with an award sticker and a dog on the cover. Trust me, that dog is going down.”

These were many of my favorite books too, ones I returned to again and again in our small rural library. How lovely to see such a tender, appreciative remembering!

#10 – When I walk in the neighborhood, there is a lawn with a gazing ball and I think about Diamond in the Window. For me, as a child in the 60’s growing up across the street from the library, Heinlein’s Have Space Suit- Will Travel started me on a lifetime of sci fi and fantasy

Great article, and as a child growing up in the 1950s and 60s you have given me a lot to read!

We grew up with my mother reading us the Oz books (ALL of them), and then in third grade she made me order The Hobbit from the school bood paper. First time for everything, and I thought it was weird. Then it came, and my reading habits changed forever.

@0: I think there is a fascinating conversation to be had about the way children’s books influence and change young readers. Oh yes. I’m old enough to pre-date most of these (although I got pointed later to the Cooper and Wrede sets and liked them), so my list of influencers is different, but it’s definitely there. I sometimes wonder about the other-track me who stuck with Heinlein juveniles and never found Andre Norton’s more … openminded … works (if only the ones that had male leads, since publishers of the time thought only boys read SF); I’m not sure I’d like that person. Books can confirm a narrow mind-set, but (as you point out in various ways) they can also help minds to open.

@21 Merona–See? It’s partly about the award sticker. See comment on the Newbery above.

My guess is that the “all the dogs in children’s books die” idea comes primarily from people who were required to read both Sounder and Where the Red Fern Grows in school. Island of the Blue Dolphins has the Newbery sticker, but I don’t think it was assigned as much as those two were circa the 1970’s/80’s. The book satirized in No More Dead Dogs, “Old Shep, My Pal,” kind of sounds reminiscent of Old Yeller, but are kids really pushed to read Old Yeller anymore?

I do think the Newbery choices are gradually getting better overall, though.

The essay has inspired me to think not only about the books that changed me in childhood/adolescence, but also about the scenes associated with that process of change and growth through reading…and to ask friends about the books/scenes that changed them in their early reading.

For me it was Heinlein. When I turned 7 I decided I was ready for books that didn’t have pictures. I asked the librarian at my local branch for a recommendation. She suggested “Red Planet.” I was seriously hooked. Ice skating on the canals, Willis. Other grade school favorites included the Narnia series and Jules Verne. Oh, not SF but sort of fantasy was the wonderful Freddy the Pig series by Walter R. Brooks. Talking animals doing regular human stuff, fully integrated in small town society. Edward Eager’s Half Magic series too. It introduced me to the laws of magic as defined in the stories.

Always love these articles because I invariably end up discovering new “old” books that I somehow never encountered. Even as an extraordinarily bookish child allowed to check out basically ‘anything’ at the library by both my mother and the librarian. ‘A String in the Harp’ is now on my wishlist. :p

My stick with it books are The Dark is Rising series for all of the myriad reasons including that stated above about the absolute nastiness of Caradog Pritchert and killing Cafal. Bran’s subsequent shunning of Will and the reconciliation, really made an impression. One of the few examples where the death of the beloved pet actually furthers the story rather than just being inevitable shock value.

Also, obviously (see username) Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave ingrained in me a love for Merlin in ALL his infinite incarnations that has stuck with me for almost 6 decades!

Another book ingrained in my beloved list is Moonheart by Charles De Lint. Tamson House was ALL of the things I had ever wished for or imagined in a house made of magic. Everything else in the story was just cream on top of the cake that was Tamson House.

Also a formative book in my character was Magic’s Pawn by Mercedes Lackey. The first book I can remember with a gay protagonist that was my entry into the magical kingdom of Valdamar. The way Ms. Lackey presented Vanyel. His struggle and awakening into both his gender preferences and the sudden agonizing onset of his magic and becoming chosen. That book is STILL powerful and I re-read all of the above every few years. Even tho I am sliding down the backside of the age hill, these books still have powerful messages and are old familiar friends.

I’m older, and only found most books without horses post-Hobbit. But I did get David and the Phoenix from an elementary school book club, and never got over it. Don’t know if it is still in print—self-immolation might be a tricky sell for today’s parents.

The Chronicles of Prydain have been mentioned a couple of times, but let me elaborate. My parents read this series to me when i was very young, and i have read it many more times throughout my life, including as an adult. It is astoundingly good, frankly the single best coming of age story I have ever read.

Taran’s growth as a person throughout the series is so grounded and realistic, and Alexander’s working never falls into simple young person drama that many other stories do. To be completely frank, I never could enjoy Harry Potter, and this series is the reason why. Not that Rowling didn’t do some things fantastically well, but the overall package couldn’t hold a candle to Prydain, end of story. I read the first 5 HP books and couldn’t help but compare to Prydain in the writing style, world building, characters, etc, and I felt HP took second fiddle to Prydain in almost everything.

I am currently reading this series to my 12 year old son, like father did to me, and he is eating it up. The characters are brilliant and scintillating without being over the top or tropey. The writing is clever – there are very frequent laughs, and the depth is something that I felt invited to use to examine my own growth over the years. Taran’s struggle to find himself in the 4th book, Taran Wanderer, is utterly profound and heart wrenching, and I resonated with it over and over again.

While I have read and loved several of the series listed here, none of them hold a candle to Prydain. Highly recommended for anyone who hasn’t read them yet!

The “Green Knowe” books by Lucy M. Boston: The first one I read, “The Treasure of Green Knowe,” was the first book I ever got “lost in.” I was reading it and suddenly realized my mother was calling me for dinner, and when I looked up, I was momentarily disoriented before recognizing the familiar surrounding of my room. I still think it may be the strongest of the series, since the author keeps it mysterious as to whether Tolly is traveling to past events or whether the people from the past are appearing in the present, or whether “past” and “present” somehow coexist at Green Knowe.

What I am getting from many of these comments is that maybe I need to plan a future essay around a Chronicles of Pyrdain reread. I haven’t read those books in decades and don’t remember many details! I suspect it would be a delight to rediscover them.

I love learning what books other people recall from their childhoods, and how so many people have the shared experience of knowing there was something, at some point, that really got under their skin. I love it.

I didn’t notice any mention of The Wind in the Willows or The Little Prince, two hugely influential children’s fantasies that I still love today (Gen Xer here). That last chapter of The Wind in the Willows lives in my heart. Madeleine L’Engle was a major influence along with Ursula K. Le Guin. I also discovered Tolkien and C.S. Lewis pretty young (Ok fine I’m a huge Tolkien geek!). My daughter, if she were here (she’s 20 and away at college), would say Diane Duane and Diana Wynne Jones (didn’t see her above either!) are authors she still rereads constantly. Those are authors, along with Patricia C. Wrede and others, I discovered as an adult and enjoy so much.

I thought I was the only person in the world to read The Perilous Gard! I love most of the books you cite. All favourites from my own childhood!

@kali, a reread of Prydain would be delightful. Do it! Make sure you include Book 6: The Foundling and Other Tales – the collection of short stories that fills in some interesting gaps from the main series, though it’s totally full of spoilers, so it’s definitely after you finish the rest.

Ah, thank you for this as this is very timely. I am a first time grandpa and the thought/dream of getting to read “A Wrinkle in Time” and the “The Little Prince) to my grandson is on my list (granted it will take a few years as he is only 1 month old)l. Those two books were influential in my reading habit that continues through today. I appreciate the pointing out of the dragon series by Patricia Wrede, I will have to read these to see when I could introduce them to him. Also, I didn’t know about the “Chronicles of Pyrdain” series. I will have to check them out as well. Wonderful article

I love The Perilous Gard with a fire that cannot be overstated. It’s tremendous. (Pope’s only other book, The Sherwood Ring, is also a fun read.)

While I know that The Grey King is more popular, I love The Dark is Rising the best in that series. The way it portrays a dark aspect to the Christmas and New Year’s holidays is mesmerizing.

And I concur with @20: The Blue Sword and The Hero and the Crown are marvelous books with fantastic female protagonists.

Wonderful post!

I haven’t read any of the books listed in the article, yet…

>7. drcox I loved reading my father’s My Bookhouse series, so much that a few years ago I found the same red editions online and made them my own.

>16. Saavik I was and remain a big fan of good animal stories. By 8 or 9 I was reading books like The Jungle Book, White Fang and The Call of the Wild, Silver Chief, Kazan, The Incredible Journey, Lad, a Dog, and more. The Hundred and One Dalmatians still tickles my funny bone, too. I despised Sounder, but loved Where the Red Fern Grows, cried over Old Yeller but cheered on his son, Savage Sam. Does anyone still read books by Jim Kjelgaard? Jean George? Joyce Stranger? Glenn Balch? Marguerite Henry? Ernest Thompson Seton? James Oliver Curwood? Walter Farley?

I loved the Prydain books, but that was after I loved animal stories, and developed a love of animal, any animals.

@Brenna – Seconding the Young Wizards series because I’ve reread the first few enough to kill my original paperbacks and stuck with the series for over 30 years (yes, it’s still going)! Check out the companion series with kitty wizards too!

@38 fuzzi AND @7. drcox I loved reading my father’s My Bookhouse series, so much that a few years ago I found the same red editions online and made them my own.

Me three!

Aside from that series, I’d like to name an author that no one else has added to this thread: George MacDonald. A librarian at the huge city library we rarely visited (back before the idea that there ought to be a colorful cozy children’s section of a library) suggested The Princess and the Goblins and I loved it, but for some reason I could never remember the title and it absolutely haunted me. That invisible thread, the queen’s stone shoes, the grandmother in the attic—I never guessed what MacDonald was paving the way for until I was much, *much* older.

I still prefer children’s literature to a lot of what is out there. So thanks to the OP for a new story to look for! (A String in the Harp)

Yes, Prydain, a 100 times yes. Book 3 is only OK but the other four are magnificent, each in different ways.

Once you read the books, you realize exactly how bad the Disney Black Cauldron adaption really was.

The only one of these I remember reading was The Grey King, and only after reading this article did I remember it.

My biggest take that I remember is that written Welsh is incomprehensible to an English speaker. Knowing what I know now of the Welsh, it would be no surprise at all that this was intentional.

I own four out of five of the list. A record for me!

It’s lovely to see so many old book friends in the [excellent] article and [eloquent] comments. I feel that books echo back and forth in time and influence us in both directions. Tamora Pierce is an excellent such influence who hasn’t been mentioned yet [until now].

I just reread one of my old favorites, The Half Brothers by Ann Lawrence, and was pondering this same issue of marketing. It had a children’s publisher and was in the children’s room, but it’s definitely a romance (ends with a marriage even!) I adored it at the age of 11ish and still do. Possibly the reason it never made it into paperback (and is thus pretty hard to find now) is no one really knew how to market it.

Everyone talks about the Newberys being “dead dog books”, but I know of at least three Newbery books with dead elephants. Anyone else know which ones they are?

Thank you! That is such a great way of putting it.

Also I did not know that about Talking to Dragons! I also read them in story universe order. I will have to read them in pub order now… I am a loud “Don’t read The Magician’s Nephew first” apologist, so I wonder if reading TTD without knowing who the father is makes up for the fun of not knowing that Cimorene and Mendenbar will fall for each other.

I read different books as a child, because by the time my English was good enough to be reading those, I was deep into Lord of the Rings, Chronicles of Amber and everything Asimov wrote about robots. But I hear you. I don’t remember a single book that “scarred” me, or “indoctrinated” me, or whatever. I remember picking new ideas, and not really noticing the stuff that now I would ascribe to the “suck fairy”, and quitting some books midway because they spoke about stuff I couldn’t relate to back then, though now I can.

Certainly, I was exposed not only to “good” ideas, but I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I learnt from books that people used to live and think differently from the way we do now. I didn’t learn that “a woman’s place is in the house” – merely that it used to be, sometimes, and some women were OK with it, though others were not. I didn’t learn that being a Jew made me a monster, but I did learn that many people used to see me that way.

From the Three Musketeers (which modern moral guardians would say I shouldn’t have been reading at 10) I learnt that friendship and courage are good and admirable. I did not learn that rape and murder are OK, though the characters do that too. From Jules Verne I did not learn that the White Brit is superior to all others, but that the world is full of wonder.

Saying “I don’t want my child to be exposed to this idea” is wrong on multiple levels. It’s an insult to the child’s intelligence and integrity. However strongly I believe in “my” ideas, I wouldn’t want a child of mine to grow up in an echo chamber. I’d want them to find out what others think, and I’d trust them to pick out the good from the bad. Even if sometimes they disagree with me. Not that I’d throw them into the world with no guidance, of course; a parent teaches by explaining, by presenting ideas, by acting in the ways they believe to be right. I do not believe my guidance so weak that exposure to one dissenting book may overturn it. If it can, then maybe I should read that book too, maybe my idea wasn’t that great to begin with.

The best thing about such articles for me is to know I wasn’t alone in living these books. Til now, I was the only person I knew who gad read and loved The Perilous Gard.

And these books are great discoveries at any age. I got A Wrinkle in Time at age 8, but found the sequels only in my 20s.

The books I read as a child constantly resonate with me decades later. Don’t they for everyone?

After reading an article about how girls are less likely to answer questions in class than boys my husband went on a hunt to find books for our four daughters where the main character was a strong girl. Dealing with Dragon series was a favorite of all four of them. I think one of our daughters even wrote to the author and was so excited to get a reply.

@47 Since no one else answered my trivia question, I’ll answer it: The Cat Who Went to Heaven, The Giver and The One and Only Ivan.